McGill University examining its connections to slavery and colonialism

July 13, 2020

With universities around the world addressing their racist past, MGill University has joined the queue as it prepares to celebrate its bicentenary next year.

The money left in James McGill’s will to fund a university was accrued from the exploitation of enslaved Black and Indigenous People.

A petition has been launched calling for the removal of the slave owner’s statue on McGill’s downtown campus and the university has appointed two Postdoctoral Research Scholars in Institutional Histories, Slavery and Colonialism to critically examine its connections to slavery and colonialism.

The one-year Fellowship is renewable.

Joana Joachim, who is pursuing a PhD in Art History, Criticism & Conservation, and Melissa Shaw, who is completing her doctorate in History at Queen’s University this year, will begin their new assignment in the fall.

“We will be looking at McGill’s connection to the Transatlantic Slave Trade and its relationship to Indigenous communities and colonialism,” said Shaw who was born in Mississauga to Jamaican immigrants. “I am a historian, so to be able to produce research findings that will help the university better understand its connections to those two objectives is what I plan to achieve. It’s a little bit difficult because sometimes people think of historians as policy makers. Being a historian is sometimes unglamorous because it’s really about doing good research and a thorough investigation. What people do with the research findings depends on the environment they are in, how dedicated they are to making a significant change and how much control they have over the range of change.”

Shaw’s preliminary archival work will assess how Blackness, Indigeneity and Whiteness informed McGill’s development from the 1800s to the 20th century.

“I am going to be looking at newspapers, private letters, past records, insurance sales and things like that,” the former Dalhousie University part-time faculty member said. “I am looking at any primary source that has a relationship to James McGill and anyone that donated to make McGill the university it has become today. There are obviously different approaches you can take about how to interpret those sources, but my main objective is to understand to what extent McGill himself or those donors were accruing their wealth.”

McGill’s Provost & Vice-Principal Academic Christopher Manfredi created the Provostial Research Scholars Program.

“As we approach the Bicentennial, I felt it was imperative to put in place an initiative that would allow us to engage in a thorough, rigorous and critical self-study conducted by experts,” he told the McGill Reporter. “I wanted these experts to be emergent scholars, given our commitment to cultivating and nourishing academic talent. At the same time, I recognize the need to do more than just understand the past. We also need to take steps to address ongoing inequities linked to the past.”

Professors Wendell Adjetey and Suzanne Morton, who are in McGill’s Department of History & Classical Studies, and Art Professor Charmaine Nelson have been chosen to supervise Shaw and Joachim’s work.

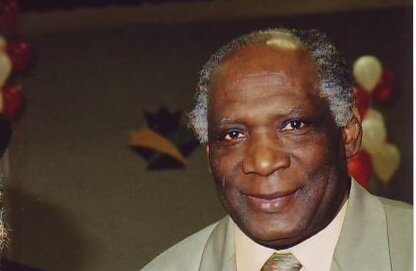

Towards the end of her undergraduate studies at the University of Toronto Mississauga Campus, Shaw was turned on to Black Canadian History taught by historian Dr. Sheldon Taylor.

“I had done mostly Western European History up until that point,” said the Queen’s University Master’s graduate. “I was really inspired by Professor Taylor’s enthusiasm for Black Canadian experiences in particular and just the plethora of information he gave to us. I didn’t realize how much Black Canadian history was there. I have nieces and nephews and I don’t want them to have that experience I had growing up of not reading or being taught about Black History in school. Even reading about Black people growing up, it was always stories about very heavy gloom, oppression and marginalization that is very much a part of the experience. However when children and people read that, they become in a way not having a sense of that you have anything to be proud of because you come from ancestors who oppressed.

“The more I study Black Canadian History and Black History in general, the more I see their strategies in ways that people carved out lives that were filled with joy, they took care of their families and they loved each other. To be able to see this pattern of resilience as opposed to in the face of oppression, I think, is a different way of reading Black History in a way that will empower future generations to know that we have much more to be inspired by. These are people who never quit.”

Shaw’s PhD dissertation, ‘Blackness and British Fair Play: Burgeoning Black Social Activism in Ontario and its Responses to the Canadian Colour Line, 1919-1939’, explores the symbiotic relationship between anti-Black racism in Canada and the rise of Black Canadians socio-political activism in Ontario.

Questioning social articulation of ‘race’ consciousness within a variety of Black Canadian organizations, it examines the ways activism initiatives claimed rights for Blacks as Canadian citizens and British imperial subjects through local, continental and Diaspora methods and networks of race politics.

Centring the ‘everyday’ acts of resistance Black Canadians employed during this period, her study considers community building as strategic and carefully crafted responses to the Canadian colour-line at the local level. It also considers the collaborations and networks local activists formed with other people of African descent in places like Detroit, New York and Washington.

“In this way, the project engages modern Canadian history and expands studies on Black internationalism during the twentieth century,” Shaw pointed out. “I am intrigued by the interconnections between intellectual and social history. As a Black Canadian woman, I am committed to honouring the complicated legacies of my resilient forebears. As a scholar of Black Canadian history, I am deeply concerned with the role of historical contingency when dealing with weaponized racial identities.”

Shaw will defend her doctorate in the fall.

Dalhousie was the first Canadian university to inquire into its relationship to slavery and race.

George Ramsay, who described Black people as ‘idle and pre-disposed for slavery’, used the proceeds of slavery to set up the university in 1818 and actively sought to banish Black refugees from Nova Scotia.

Last year, Dalhousie apologized for its founder’s racist views.

In April 2019, Queen’s University formally apologized for the Faculty of Medicine unjust decision in 1918 to expel 15 students, the majority of them from the Caribbean.

The ban, enforced until 1965, was instituted to demonstrate alignment with discriminatory policies favoured at the time by the American Medical Association, the organization that ranked medical schools in North America.